1. Introduction

The aim of this White Paper is to explain the various coding systems in use throughout the air transport industry for identifying locations, and to illustrate some of the strengths and weaknesses of the various systems used.

2. Background

The world’s scheduled airlines currently serve some 4,000 airports in around 200 countries and territories. Airports range widely in terms of size and facilities, and the terminology used to describe a specific airport can also vary depending on the context. For example, the term "London Airport" is generally understood to mean Heathrow Airport, located some 15 miles west of the UK’s capital city. However there are a number of other airports around the capital which can legitimately claim to be a "London Airport" - and of course an airline serving London (Ontario) or London (Kentucky) will have yet another interpretation.

It follows, therefore, that the industry has had to find some way of referring unambiguously to a specific airport, and this is normally done by using a location identifier.

3. Location Identifier Systems

While many countries and other aeronautical agencies have in the past devised systems of identifiers for airports, airfields and other aviation-related facilities, there are four main systems in use today, two of them worldwide in scope and the other two specific to the USA and Canada.

All four systems have the same aim - to provide an unambiguous means of referring to specific airports. However there are a number of important differences between the rules adopted by each of the systems.

Each is considered in turn below.

4. IATA - International Air Transport Association

IATA’s stated mission is "to represent and serve the airline industry", and so its focus is on commercial air transport. Originally founded in 1919, it now groups together nearly 270 airlines which between them fly over 95 percent of all international scheduled air traffic.

IATA Resolution 763 states that all member airlines and CRSs shall use the location IDs published three times per year in the "Airline Coding Directory"; principal applications are for ticketing, reservations and baggage handling, together with numerous other uses.

Location IDs covering airports in the United States are assigned by IATA in conjunction with the Air Transport Association (ATA) - the trade organisation for the principal US airlines.

Main features of the IATA/ATA location identifier system are:

- All codes are combinations of three letters (e.g., JFK)

- Approximately 50 combinations are reserved, and not available for assignment to airports (e.g., HDQ, QZX, ZZZ, etc)

- Wherever possible, IATA assigns codes which coincide with the first three letters of the location name (e.g., BOGota, SINgapore, SYDney) or at least with the first letter of the name. Codes may also correspond to less obvious historical associations for a location (e.g., ORD, MCO). In other cases, the first letter of an airport’s name is omitted and subsequent letters used (e.g., cORK, wILMington)

- Codes may also be assigned to non-airport locations such as rail and bus stations and other "off-line points" (such codes normally start with Q, X or Z)

- Codes are considered permanent, and are rarely reused; a standard exception to this is when a new airport such as Denver or Munich is constructed to replace a city’s current airport, and the existing code for the previous airport is transferred

- Codes for US airports are normally (but not always) the same as the FAA-assigned three-letter codes for the same location (see below for examples of exceptions).

- Codes for Canadian airports are normally (but not always) the same as the Transport Canada-assigned three-letter codes for the same location (see below for examples of exceptions).

- By convention, heliports are often assigned codes starting with J, though this is not mandatory

- A location may, in rare cases, have more than one code assigned to it simultaneously.

- The IATA resolution also makes reference to "metropolitan areas", which can also be allocated codes in the same sequence. The resolution offers no definition of these, although it can be inferred from the Airline Coding Directory that a metropolitan area contains two or more locations, each of which has an assigned IATA code. It is unclear as to whether these locations must both be airports or whether a metropolitan area may contain, for example, an airport and a bus or rail station. On one hand the resolution refers to "… a request to remove an airport from a metropolitan area comprising only two airports and the consequential dismantling of that metropolitan area" - which implies that a metropolitan area must consist of two or more airports. However there are many examples in the Airline Coding Directory of metropolitan areas comprising a single airport plus one or more non-airport locations (e.g., BHX, BTS, BUF).

- The resolution also says that if a metropolitan area is served by only one airport, the same code is used for the area and the airport; if an area is served by more than one airport, each airport will have its own code, and the code for the metropolitan area will be either one of the airport codes, or a unique code of its own. It follows that if a location "belongs" to a metropolitan area with a different code (eg ORD/CHI) then there must be other locations belonging to that area (in this case MDW, PWK, etc.).

- For many applications, it is convenient to consider every location as belonging nominally to its own metropolitan area (ie each location will have both a location code and a "city" code).

5. ICAO - International Civil Aviation Organisation

ICAO Document 7910 - Location Identifiers contains codes allocated by national governments, on behalf of ICAO, to airports, airfields and other facilities such as ATC and weather stations.

Main features of the ICAO location identifier system are:

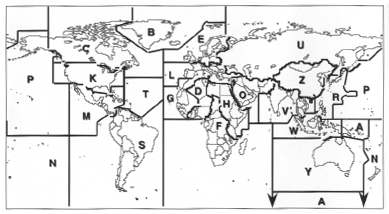

- All codes are a combination of four letters (e.g., LIRF)

- The first two letters of the code represent the region and country (for example, those starting with EH are allocated to Europe/Netherlands, etc). The only exceptions to this are codes starting with K, which are allocated to the USA, and those starting with C (Canada), where the second letter has no geographical significance.

- The remaining letters represent the airport or facility, and in many cases are at least partly mnemonic (e.g., EHAM is Amsterdam). For codes starting with K and C, the remainder corresponds to the national three-letter code allocated by the FAA and Transport Canada respectively (these are often, but not always, the same as the IATA allocated codes).

- Codes starting with I, J, Q and X are not used (though those letters may be used in the other positions).

- Codes are not normally re-allocated.

- A location may, in some cases, have more than one code assigned to it simultaneously, for example civil airports which are co-located with military bases.

6. FAA - Federal Aviation Administration

The FAA allocates location identifiers to airports, navigation aids, weather stations and manned ATC facilities within the United States and its jurisdictions. These are coordinated by the National Flight Data Center in Washington DC.

Main features of the FAA location identifier system are:

- Codes with a combination of three letters are allocated to airports which satisfy at least one of the following criteria: they have manned ATC facilities, they receive service by scheduled airlines, or they are designated airports of entry.

- Codes with a combination of one letter and two digits are assigned mainly to other public-use airports. The letter may be in the first, second or last position (e.g., C35, 4A6, 51R)

- Codes with a combination of two letters and two digits are assigned to private-use airports. The two letters are always contiguous, and may appear in the first/second, second/third, or third/fourth positions (e.g., CA40, 2MN3, 34PA). The letters represent the state in which the facility is located.

- Codes with a combination of one digit and two letters are assigned mainly to special-use locations and some public-use airports. The digit always precedes the letters (e.g., 5BK)

- Three-letter FAA codes starting with N are assigned by the US Department of the Navy, and are normally allocated to Navy, Marine Corps or Coastguard facilities (e.g., NHK).

- Facilities within 200nm of each other will not be allocated codes which share more than one letter position in common.

- Where a four-letter ICAO code starting with K exists for a location, its FAA three-letter code is identical to the last three letters of the ICAO code (e.g., KMIA/MIA)

- Where a three-letter IATA code exists for a location, its three-letter FAA code will usually be identical (e.g., MIA), but may be different. At one time the IATA used GNY for Granby, Colorado, whereas the FAA has always used GNB).

- The FAA may use a code for an airport in the USA while IATA uses the same code for a completely different airport elsewhere (e.g., the FAA once used BAK for Columbus, Indiana, whereas IATA use the same code for Baku, Azerbaijan).

7. Transport Canada

Transport Canada allocates location identifiers to airports within Canada.

Main features of Transport Canada location identifiers are:

- Codes are either a combination of three letters, or two letters followed by a digit. Three-letter codes start with Y or Z; alphanumeric codes start with any letter other than G, H, I, L, M, O, Q, R, U, V, W, X, Y or Z, and use the first letter to indicate the approximate location.

- Where a four-letter ICAO code exists for a location (starting with C), its Transport Canada three-letter code is identical to the last three letters of the ICAO code (e.g., CYVR/YVR). It follows that locations with alphanumeric Transport Canada codes do not have corresponding ICAO codes assigned.

- Where a three-letter IATA code exists for a location, its three-letter Transport Canada code will usually be identical (e.g., YWG/YWG), but may be different (e.g., IATA uses QBC for Bella Coola, BC, whereas the Transport Canada uses YBD).

- Transport Canada may use a code for an airport in Canada while IATA uses the same code for a completely different airport elsewhere (e.g., Transport Canada use YAS for Kangirsuk, QU, whereas IATA use the same code for Yasawa Island, Fiji).

updated: Feb 28, 2017 by AirportGuide.com

based on original work by AvGen Limited. July 2001